Thursday, October 18, known as Taite 18 o Oketopa in Māori, we come together to celebrate the strength that comes from unity —a bond that connects us all.

“Ēhara tāku toa i te toa takatahi, engari he toa takitini.”

Translation: My strength is not from one person, but from many. Meaning: We are stronger when we work together; strength comes from unity.

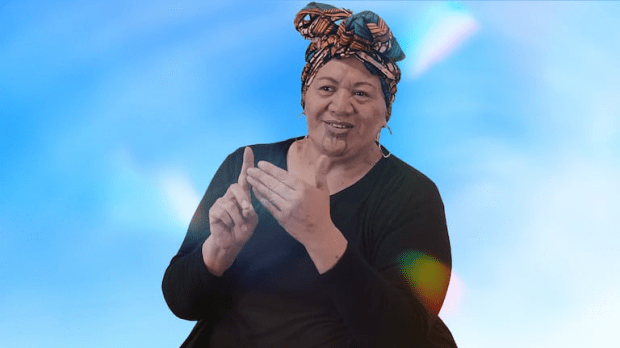

Stephanie Awheto

Ngaati Ruanui Taranaki

Iwi – Ngaa Ruahine

Haapu – Tamaahuroa titahi

Ko ngā hui pēnei i ēnei ngā wā kia tangi ki ngā mate. Gatherings like these are the times for remembering the dead. Stephanie – te kaiwhakamaori reo toru tuatahi mo te Tāngata turi i Aotearoa. (In English, Stephanie was the pioneering first trilingual interpreter for the Tāngata turi in New Zealand, a role of immense significance and impact.)

I was reflecting on the past when I first met her in Hamilton in the late 1980s and 1990s. A brief History of the Deaf Community in Hamilton: Back in the 1980s and 1990s, there was no Deaf service or organisation for the Deaf community and no interpreter for the D/deaf people/Tāngata (Māori Deaf people) when I was a BNZ Data Entry Officer. At Melville Intermediate School, the late Patrick W. Thompson was my classmate in the Deaf Units in the late 1970s. My sister studied in a Māori course and other classes at the Waikato Teacher College. Then, my mother learnt to study in a Māori course at Waikato University.

Patrick’s curiosity about his Māori background and Te Reo Māori at school led him to seek Stephanie’s help. Her unwavering dedication to helping him reconnect with his roots is a shining example of her commitment to the Deaf and Māori communities. This connection blossomed into a warm relationship, with Stephanie welcoming Patrick into her whānau over many years until his passing in 2014.

Stephanie completed her Interpreter course at AUT in 1996, and she and her young whānau moved to Hamilton in the early 1990s. The Deaf Association of NZ: Hamilton Branch (later changed to Deaf Aotearoa) opened in Hamilton in 1991.

No official languages existed for the D/deaf people and Tāngata Turi (Māori Deaf people) in Aotearoa until 2006. In 1987, Te reo Māori was made an official language, followed by NZSL (New Zealand Sign Language in 2006. The main problem was where the Te reo language is, as in sign language for the Tāngata Turi (Māori Deaf people). As you see, there was never an original sign language by the Tāngata Turi (Māori Deaf people) for over a hundred years. Proto-Polynesian, a language spoken about 2,000 years ago, is the ancestor of all Polynesian languages. Māori people arrived in Aotearoa a thousand years ago, and their language was Te Reo. Then, the English settlers/immigrants came to Aotearoa with their English-speaking language, but there were several minor languages spoken, such as Dutch, Norwegian, Danish, and even Polish. In 1867, the Government and Education banned all Māori children from speaking te reo in schools.

How does sign language come here? Who was/were the people who used sign language here? It is the D/deaf people themselves who brought sign language back as ‘loan sign language’ to Aotearoa/New Zealand from the boarding schools in Australia, the United Kingdom and the USA. They created sign language like Pidgin-Creole sign language when encountering other D/deaf people in different districts, businesses/trade around Aotearoa. NZSL is more or less closely related to AUSLAN (Australian Sign Language) than BSL (British Sign Language). We need to have actual records of Pidgin-Creole sign language here while linguists continue researching and understanding the past. Sign language was banned through schooling at Van Asch, Titirangi School for the Deaf, Kelston School for the Deaf and in different regions of the North Island Deaf Unit Schools in the past due to the Second International Congress on Education of the Deaf, an international conference of deaf educators held in Milan, Italy, in 1880. Today, it is known as the Milan Conference or Milan Congress to many D/deaf people worldwide.

Fast-forward: Stephanie was talking to Patrick by learning sign language. She was confused by one or more sign languages translated in English to Te reo—hang (in Sign Language as a hand grasped in front of the neck) vs. hangi (cooking foods on top of the heated rocks in the buried pit) in Te Reo without sign language. Patrick described what he was trying to explain from his sign language to Te Reo. Many of the D/deaf people who sign for ‘hang(i) were exploited or offended by any Tāngata Māori around Aotearoa.

He waka eke noa

A canoe which we are all in, with no exception

Stephanie’s decision to become a trilingual interpreter for the Tāngata turi Māori was a significant step towards bridging cultures. Since Te Reo became an official language in 1987, there has been no trilingual interpreter for Tāngata turi Māori. The gap was particularly felt during critical cultural events such as the marae ātea, hui, and the significant landmark of the Te Tiriti o Waitangi. Stephanie’s role as a bridge between cultures not only facilitated communication but also fostered a deeper understanding and respect for the Māori Deaf community.

Ko taku reo taku ohooho, ko taku reo taku mapihi mauria

My language is my awakening, my language is the window to my soul.

Stephanie travelled around Aotearoa as a trilingual interpreter in hui, the marae ātea, Māori Deaf development activities at the marae ātea, and at the university where I took my BA in Arts and Stephanie mentored trilingual Māori interpreters/Te Reo Rotarota Māori interpreters. Stephanie was there to interpreted when I received my BA degree at the University of Waikato – the

Te Kohinga Mārama Marae.

Whaiwhia te kete mātauranga

Fill the basket of knowledge.

Patrick told Stephanie that many Tāngata turi Māori lost their Māori identities, culture, Iwi and Hapu backgrounds, Te Reo, and, of course, Te Tiriti o Waitangi (known in English as the Treaty of Waitangi). This loss was a result of historical factors such as the suppression of Te Reo in schools and the influence of the Milan Conference. Patrick and Stephanie travelled around Aotearoa to meet many Tāngata turi Māori before setting up the first Tāngata turi Māori Hui in Orakei in 1993. I was overseas when Patrick and the organisers created the first National Māori Hui, introduced in 1993. Stephanie, her supported whānau and her colleagues supported those (Tāngata turi Māori) wanting to reconnect with their Māoritanga and reclaim matauranga Māori. It was critical and a challenge for everyone to work together as a team.

https://www.nfdhh.org.nz/post/te-reo-maori-and-new-zealand-sign-language

Rūaumoko Marae

The opening of the first Rūaumoko Marae on December 4 at Ko Taku Reo Deaf Education NZ (formerly Kelston Education for the Deaf), Auckland, thirty-two years ago, was a significant milestone. It brought many benefits to all Tāngata turi Māori students and communities, marking a proud moment in our history.

He aha te mea nui o te ao? He tangata! He tangata! He tangata!

What is the most important thing in the world? It is people! It is people! It is people!

This whakatauki talks about the importance of human connection and relationships. These are what create community and enable people to flourish. It values the human being in all of us and reminds us of what is most important—not money, not success, not a job or a thing—it is people.

Kua hinga te totara i te wao nui a Tane

The totara has fallen in the forest of Tane.

Ahakoa nga uaua, kia toa, kia kaha

Kia manawanui.

When you find things in life are difficult, be strong, stand tall and be of a great heart.

“Nā koutou i tangi nā tātou katoa.”. When you cry, your tears are shed by us all.

E aroha ana ki a koe me te whanua i te ngaronga o Stephanie.

Permission granted from Marshall to post this article along with his comments.

I know she had a strong working relationship with all involved at NZDAssociation and multiple times with the Māori Deaf as a Whole. Your wisdom is welcome tku Tautoko te reo Māori is what she would be signing atm. Tku. Yes, what a nice recall on her pathway to Trilingual Sign Language Interpretations

Yes, she did do all that to get it done.

I’m grateful you’ve taking me back beyond the earliest times, tku

Ae sad but we must continue to continue on. I know we have have a big whole left behind since Steph’s send off.

He mihi nui ki a koe e Stephanie mo te tohutohu me te whakaako i a au mo te ao Maori, tikanga, me Te Reo i a au e ako tonu ana, e tuhi ana, e whakaako ana i nga wa e hiahia ana ahau ki te tangata Maori mai i taku waahi mahi me te Poari Kaitiaki ki a au.

In English – Thank you, Stephanie, for mentoring and teaching me about the Māori world, culture, and Te Reo as I continue to learn, write, and teach when I need a Māori person from my workplace and the Trust board with me.

You must be logged in to post a comment.