Ratapu 21 o Oketopa 2025, as in Māori (Sunday, October 21 2025), we come together to celebrate the strength that comes from unity —a bond that connects us all, showcasing the unity and stability that is inherent in Māori culture.

He kai kei aku ringa

There is food at the end of my hands

Said by a person who can use their basic abilities and resources to create success.

“Ēhara tāku toa i te toa takatahi, engari he toa takitini.”

Translation: My strength is not from one person, but from many. Meaning: We are stronger when we work together; strength comes from unity.

Māori songs, a vibrant part of community events, find their fullest expression through kapa haka, concerts, Marae, welcome, blessing, and many other performances. Kapa haka, a traditional Māori performing art form from New Zealand, is a powerful means of cultural expression, combining song, dance, and chanting to convey the depth of Māori identity and history. The name itself, ‘to form a line’ and ‘to dance’, hints at the emotional and cultural significance of this art. Kapa haka includes various elements such as powerful haka (war dances), graceful action songs (waiata-ā-ringa), and choral singing, often featuring rhythmic movements like foot-stamping, body slapping, and tongue protrusions. These performances, rich with emotional depth and the beauty of Māori culture, are a vital way for Māori people to showcase their cultural heritage and are practised in schools, communities, and at major events like the Te Matatini competition. The beauty and emotional depth of these performances will surely leave you feeling connected and appreciative of the Māori culture.

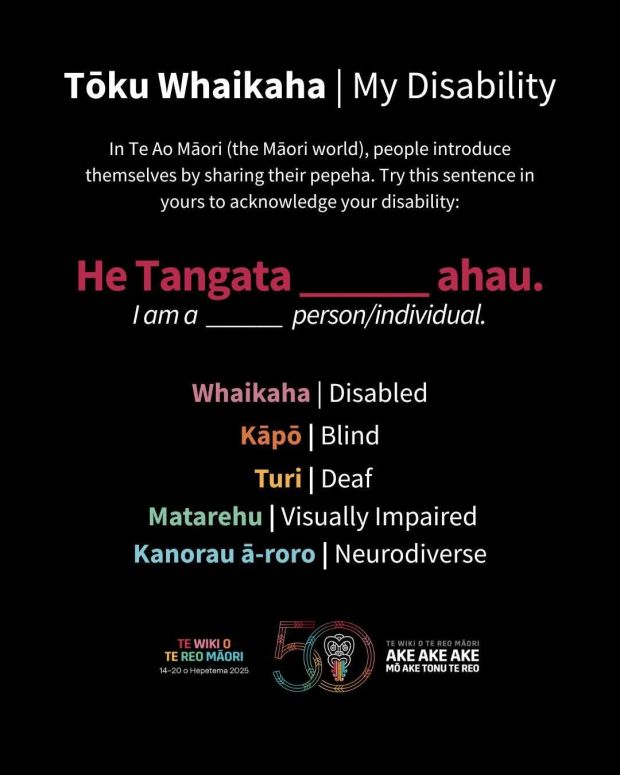

Several songs are available in NZSL with Māori concepts, and this is just the beginning for them to learn more about their background and culture. For example, a Pepeha is not just a set of words; it’s a powerful tool that connects us to our Iwi (Tribe), Manga (ancestral mountain), awa (river), hapū (sub-tribe), and meeting place (Marae), reminding us of our rich Māori heritage. The educational value of the Māori language and concepts will surely leave you feeling informed and enlightened.

The song, which Te Aroha in NZSL Te Reo concepts sang, is now available for everyone, including Taangata Turi Maaori.

Today, we have the new Māori Kuini (Queen) – the youngest of the siblings and their father, Kiingi Tūheitia (full name Tūheitia Pōtatau Te Wherowhero VII), who passed away on August 30, 2024.

Nga wai hono i te po Pōtatau Te Wherowhero VIII (Nga wai hono i te po Paki) is the youngest daughter of Tūheitia. She is a direct descendant of the first Māori king, Pōtatau Te Wherowhero, who was installed in 1858. Nga wai hono i te po’s first language is Te Reo Māori, and she is deeply immersed in Māori culture and traditions from an early age. She loves Kapa haka, having taught it in her second year at the University of Waikato. There is a bit of history behind her name’s meaning, as told to her by her grandmother, Te Arikinui Dame Te Atairangikaahu, the only previous Māori Kuini (queen).

Te Atairangikaahu was on the annual Tira Hoe Waka canoe journey down the Whanganui River and had stopped for the night at Parikino Marae when she heard that her granddaughter had been born. She asked Whanganui kuia Julie Ranginui for a name for the baby, and together they settled on “Nga wai hono i te po ” (meaning “the waters joining in the night”), referring to the meeting of the Waikato River people with the Whanganui River people that night.

@petervaneeden3651, a place to stand makes sense; everyone should have that right over their affairs. Tūrangawaewae is one of the most famous and influential Māori concepts. It means foundation, foot, and translates as ‘place to stand’. Tūrangawaewae are the places where we are strong and connected. They are our foundation, our place in the world, our home.he waahi e tu ai Ko Tūrangawaewae tētahi o ngā ariā Māori rongonui, tino kaha. Ko te tikanga ko te turanga, ko te waewae, ka whakamaoritia he ‘wahi hei tu’. Ko Tūrangawaewae nga waahi e kaha ai tatou, e hono ana. Ko ratou to tatou turanga, to tatou waahi ki te ao, to tatou kainga.

There was a waiata (song) I recall by one of the lecturers at the University of Waikato, Hirini Melbourne. Hirini Melbourne was from the Tuhoe and Ngati Kahungunu tribes. From 1978, he was on the staff of the University of Waikato, becoming an Associate Professor and Dean of the School of Māori and Pacific Development. Hirini developed them into a song of remembrance for one of his students who had died after facing numerous adversities. In 2002, Melbourne was awarded an Honorary Doctorate from the University of Waikato. He was appointed an Officer of the New Zealand Order of Merit in the 2003 New Year Honours, for services to Māori language, music and culture, just before his death a week later.

Today, there are a couple of waiata along with NZSL Te Reo Māori concepts.

You must be logged in to post a comment.